I always find it helpful to discover that someone of great attainment or laudable character, someone I’ve admired, has struggled with mental illness. It’s one thing to know they overcame whopping opposition out in the world. It’s another to learn that they did so while grappling with the maladies that hacked their wetware and harrowed their soul.

Some of these people, when beaten way down, pushed up from the mat bruised and bloody, woozy with late-round fatigue, and started kicking ass on both fronts—pummeling injustice on the outside while whaling away at their private demons. Talk about profiles in courage.

Case in point: I was both unsettled and cheered to learn that Martin Luther King struggled with serious depression. Unsettled, of course, because it’s always sad to learn that another person has had to go through that kind of anguish. In his incisive book A First-Rate Madness, Tufts Professor of Psychiatry Nassir Ghaemi describes how King attempted suicide twice as a child, and sometimes grew so despondent that his staff urged him to seek psychiatric help.

Case in point: I was both unsettled and cheered to learn that Martin Luther King struggled with serious depression. Unsettled, of course, because it’s always sad to learn that another person has had to go through that kind of anguish. In his incisive book A First-Rate Madness, Tufts Professor of Psychiatry Nassir Ghaemi describes how King attempted suicide twice as a child, and sometimes grew so despondent that his staff urged him to seek psychiatric help.

But I was also cheered to learn about King’s depression, because it makes his triumphs seem even more monumental. It’s another example of how meaningful, even heroic historical achievement is possible for people beleaguered by this disease.

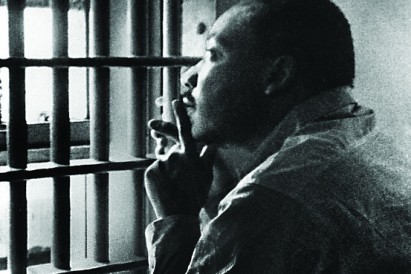

Dr. King was spiked to one of his lowest points as he sat in the Birmingham jail on Good Friday 1963. In his role as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, he’d been waging a nonviolent campaign of sit-ins and marches to protest the town’s brutal segregation.

Birmingham was one of the most racist cities in arguably the most racist state of the country. A few months before King’s campaign there, Governor George Wallace had spewed his acid challenge to civil rights leaders:

I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow and segregation forever!

King and his compatriots answered that challenge with direct action. The sit-ins and marches started on April 2. A week later, when the city obtained a state circuit court injunction against the protests, King decided to defy the authorities and get arrested. He was thrown into solitary confinement, denied an opportunity to call his wife, locked for days in a grimy cell with no mattress.

But what hammered him down even harder than those conditions was a letter he read in a newspaper a guard smuggled into the jail. Entitled “A Call for Unity,” the letter was penned by a group of white Birmingham clergymen. It slammed the protest leaders as outside agitators and questioned their right to organize a campaign in Birmingham. It urged “patience” on the city’s black citizens, who had already suffered vicious, humiliating segregation for decades. It said the civil rights issues should be addressed only by courts. The demonstrations being held that week, said these clergymen, were “unwise and untimely.”

The letter fronted as sensible Christian concern. But it was actually a mealy-mouthed rebuke mixed with a demand for Uncle-Tom complacence.

When King’s lawyer, Clarence Jones, visited him in jail, he became worried. King was unshaven, dirty, downhearted. But what Jones didn’t know at the time was that King had already begun to fight back.

William James, who struggled mightily with depression himself, pointed out that hostile provocations can be potent medicine for the kind of dejection King was suffering. When “the loving and admiring impulses are dead,” he observed, “the hating and fighting impulses will still respond to fit appeals.”

When someone unjustly upbraids you, when some bull-goose shot-caller or tomfool Pharisee tries to say your righteous efforts are wrong, they might actually be doing you a favor. That sharp nasty spur might be just what you need to gin up your grit and come out swinging.

Dr. King did just that, by crafting one of the most consequential protest messages in human history. In his Letter from Birmingham Jail, he strikes a perfect balance between hard-nosed prophetic anger and even-handed, ironclad, airtight polemic.

MLK biographer Jonathan Reider describes how, after plunging down into a “kind of depression and panic combined,” King reads the clergymen’s boneheaded letter and—shazam!—“suddenly he’s rising up out of the valley, up the mountain on a tide of indignation…”

MLK biographer Jonathan Reider describes how, after plunging down into a “kind of depression and panic combined,” King reads the clergymen’s boneheaded letter and—shazam!—“suddenly he’s rising up out of the valley, up the mountain on a tide of indignation…”

First on the margins of the newspaper where the clergymen’s letter was printed, and then on toilet paper—the only things he has to write on in his dingy cell—King the “furious truth teller” begins to compose what Reider calls his “black man’s cry of pain, anger and defiance.”

The letter is charged with a fierce refusal to back down. It’s hot with King’s burning demand for desegregation without delay. Part of what made it such a historically effective piece of social rhetoric was its fiery melding of outrage and erudition. King cited Socrates, Jefferson, Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich. He used these august voices of freedom, democracy, reason and spiritual justice, along with his own eloquence and incontestable logic, to explain his rationales for direct action in Birmingham.

Reider observes that Dr. King teased out “latent themes of deliverance from an otherworldly religion, shifting attention from redemption in the next world to defiance in this one and fortifying faith that ‘God will make a way out of no way.’” This letter used Christian ideals and language for several key purposes. First, it deftly exposed the clergymen’s cowardice and hypocrisy without a hint of coarse name-calling. More importantly, it offered a spirited, flawless defense of the Birmingham campaign and the larger civil rights movement of which it was a stratospheric tent-pole.

Bull Connor’s redneck deputies locked King up and his own blue devils kicked him down. But the Birmingham brass couldn’t have known what old Martin had in store once they put him in stir. This resurgent prophet of justice transcended icebox despair and vanquished his detractors with badass bravura.

In Martin Luther King, we see how fire in the belly kindled freedom in the nation. You’d be hard-put to find or tell a more inspiring story than that.